The teaching hours transfer window

Addressing the annual headache of academic workload allocation. Like the football transfer window, the teaching transfer window is about finding the right fit for both staff and programmes.

- Home

- / Insights

- / Knowledge sharing

- / The Open University research on teaching practice feedback

The Open University research on teaching practice feedback

Authors

Allan Mooney CMBE

Senior Lecturer, Open University Business School

Dr Janette Wallace

Senior Lecturer, School of Life, Health & Chemical Sciences, Open University

The latest scholarship research within the Open University suggests that monitoring and feedback can enhance teaching practice.

The UK Quality Code for Higher Education explicitly refers to the need for assessment and feedback to be “purposeful and supports the learning process” (QAA, 2018).

Like many Higher Education Institutions (HEI), The Open University (OU), as part of its quality assurance (QA) processes, uses a process called Monitoring to review a sample of marked assessments and provide feedback to tutors on the grading and feedback provided to students. This process provides many benefits to module teams, tutors, and students. Module teams benefit from observing how assessments are interpreted and marked. Tutors receive feedback on their marking and student feedback. Students also benefit from knowing their assessments are part of a thorough QA process. For the purpose of terminology, tutors in the OU are referred to as Associate Lecturers (ALs).

Associate Lecturers are managed by Student Experience Managers (SEMs) and Staff Tutors (STs).

Research methodology

A large-scale survey was undertaken with the use of an online questionnaire to all monitors (who provide feedback on marked assessments) and monitees (who receive feedback on their marked assessments). This survey was sent to all four Faculties of the University, including the Faculty of Business and Law (FBL), Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences (FASS), Faculty of Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM), and Faculty of Wellbeing, Education and Language Studies (WELS).

248 (12%) monitors and monitees responded to the large-scale anonymous survey that explored the monitoring process. Of those 143 (58%) were monitees, 13 (5%) were monitors and 91 (37%) were both monitees and monitors.

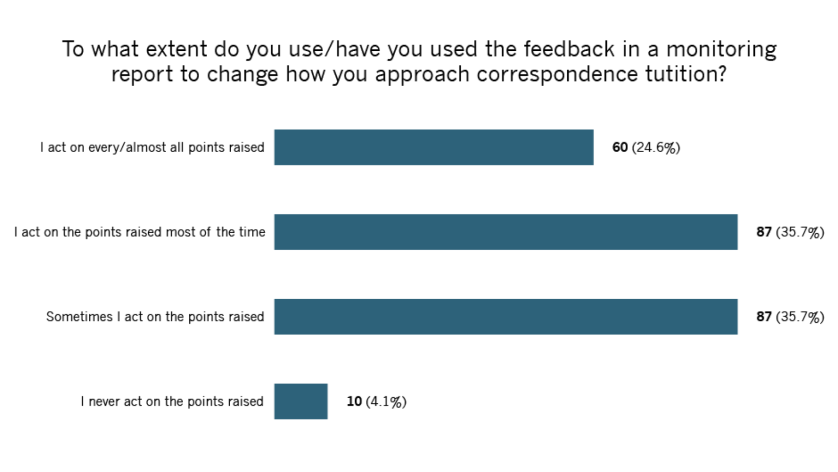

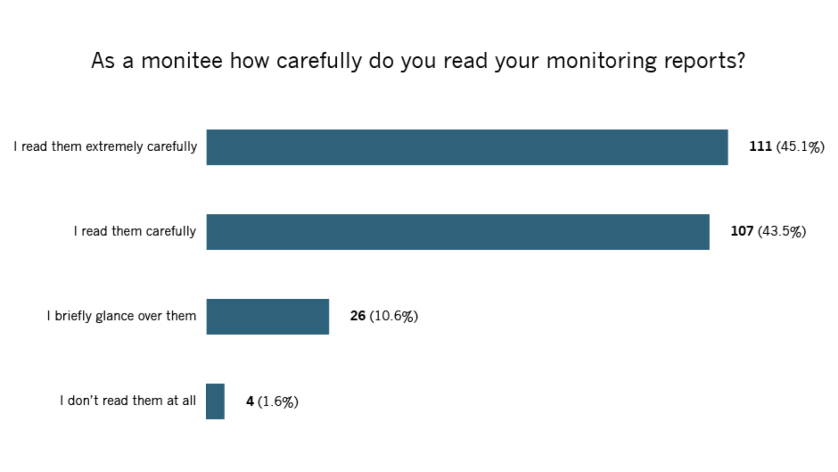

This pan-university scholarship project showed that TMA monitoring has an impact on correspondence tuition and thus student experience. 89% of the monitees who responded had read their monitoring reports carefully or extremely carefully and almost all (96% )said they acted on the points raised to some extent.

Some of the comments on the qualitative data included a monitee saying they had “incorporated suggestions around feeding forward for next assignment” and another monitee had “given more praise”. In addition, 94% of monitors surveyed stated they felt that the points they raised in the monitoring report were acted upon all or some of the time.

One monitor said, “I have had ALs contact me and say they have changed their practice for the better following feedback.” And another stated “One wonderful tutor responded…and we have had long discussions about how we mark and teach..”.

Whilst there are benefits to receiving the report, it can also be daunting.

It is clear from the research that monitors and monitees benefit from the process but receiving monitoring feedback can be a daunting experience for some; “Being assessed for performance by one's colleagues can be humiliating and engender bad feeling.” said one monitee.

There are two categories that the monitors can use in the monitoring report in relation to the grading awarded and the feedback provided. These include; meets or exceeds requirements or requires further exploration.

4% of monitees who responded did not read their monitoring reports at all. In addition, some monitors did not use both categories with 18.4% of respondents only using ‘meets or exceeds requirements’. One monitor commented “I feel that the 'requires further exploration' category puts me in a position where I am criticising my colleague's work, so I don't use it.”

Ridge & Lavigne (2020:18) cited ‘collaboration among teachers as one of the major reported benefits of peer-to-peer feedback.’ This is further supported in the works of (Jao, 2013; Koch, 2014; Phillips & Glickman, 1991; Pollara, 2012; Porras, Diaz, & Nievens, 2018). These benefits are not being fully realised in the process with 4% of monitees not reading their feedback and 18% not providing full feedback across both categories.

Given the value and impact of monitoring, monitors must be trained appropriately for this role.

What about the training provided?

Our research also evaluated the OU monitoring training provision, it found that only 40% of monitors had completed this training and worryingly 9% couldn’t remember if they had completed the training at all. Although 98% of those who had completed the training felt the training fully or somewhat equipped them for their monitor role. The lack of engagement with the monitoring training highlights a potential issue around the communication and recording of the training provided.

What if things don’t go well and there are disagreements?

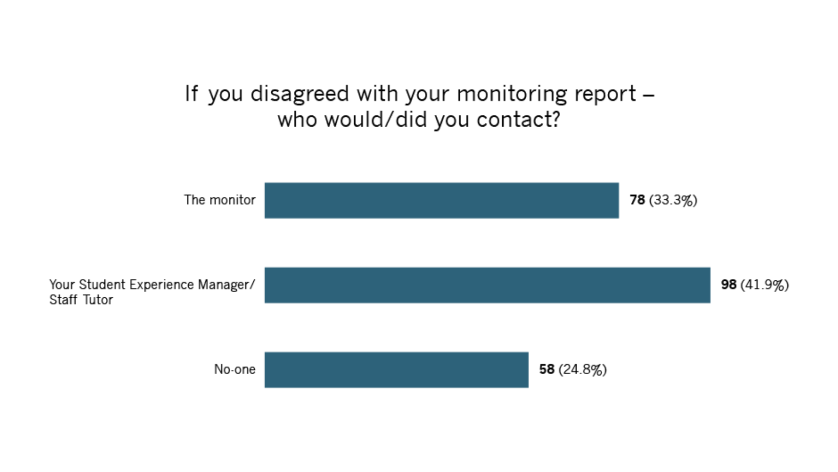

It is recognised that differences in opinion can exist in peer feedback processes. As highlighted by Ridge & Lavigne (2020:18) ‘considering the practice of peer feedback, we might consider that peers could possibly provide misleading or inaccurate feedback.’ Our own study found that nearly a quarter of tutors who disagreed with the monitoring report took no action at all.

Whilst 33% did in fact contact the monitor, 42% contacted their SEM/ST (Student Experience Manager, Staff Tutor). This does present an opportunity to promote further dialogue between the monitor and the monitee. This is further supported by comments from monitors and monitees;

“It would be good to have informal discussions about the monitoring process with other monitors and monitoring should be a dialogic process, encouraging collaborative discussion and feedback between ALs, monitors and line managers.”

Strong themes emerging from the research emphasised the importance of collaborative dialogue, mutual respect, and supportive discussions as key elements of the peer feedback process.

Call to action

Providing feedback on teaching and assessment practices is essential in Higher Education Institutions. Within the Open University monitoring is also an integral part of the Open University’s tuition model. This Call to Action is equally applicable to all Higher Education Institutions providing peer feedback to improve their teaching practices.

What can the Open University do to encourage both monitors and monitees to engage fully with the process?

Promote and encourage more ALs to complete the monitoring training or refresh their skills.

Encourage more ALs to take on roles as monitors to support their own development and those of their peers.

Encourage all monitees to read and respond constructively and openly to their reports.

Encourage dialogue between the monitor and the monitee

For more details about the research please contact [email protected] or [email protected].

References

Jao, L. (2013). Peer coaching as a model for professional development in the elementary mathematics context: Challenges, needs and rewards. Policy Futures in Education, 11(3), 290– 297. https://doi.org/10.2304/pfie.2013.11.3.290

Koch, M.-A. (2014, January 1). The relationship between peer coaching, collaboration and collegiality, teacher effectiveness and leadership (doctoral dissertation). Walden University

Monitoring Website (2024), Website: TMA Monitoring | learn3 (open.ac.uk) Accessed 150524

Nieland, S. (2020) Making the most of monitoring. http://www.open.ac.uk/blogs/FASSTEST/index.php/making-the-most-of-monitoring/ (accessed 11 June 2021)

Phillips, M. D., & Glickman, C. D. (1991). Peer coaching: Developmental approach to enhancing teacher thinking. Journal of Staff Development, 12(2), 20–25

Pike et al (2016). TMA Monitoring: Good practice and training. https://openuniv.sharepoint.com/sites/units/lds/scholarship-exchange/Lists/projects/DispForm.aspx?ID=312 (accessed 14 June 2021).

Ridge, B. L., & Lavigne, A. L. (2020). Improving instructional practice through peer observation and feedback: A review of the literature. Education Policy Analysis, P18 Archives, 28, 61. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.28.5023

Tatlow-Golden, M. (2020) E102 Monitoring Project, informal communication.