Chartered ABS responds to the DfE’s technical consultation on the International Student Levy

The Chartered ABS has submitted its response to the Department for Education’s technical consultation on the International Student Levy.

Decolonisation and diversification of the curriculum in UK business schools

Authors

Professor Sally Everett CMBE

Director, ILEAD at King’s Business School

Rachael Carden CMBE

Dean, School of Business and Law, University of Brighton

Dr Kenisha Linton-Williams CMBE

Associate Professor of Management, Greenwich Business School

If you have still to complete this survey on behalf of your business school, you can do so by clicking here.

Context

Students from Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) backgrounds are well represented in UK higher education institutions (HEIs), but their retention, attainment and progression are significantly lower than that of White students. Consequently, HEIs have been challenged to move beyond access or equality of opportunity, and instead to focus on student success and equality of outcome (AdvanceHE 2022; McDuff and Barefoot 2016; Office for Students 2021). Consequently, decolonisation and diversification* of the curriculum have emerged as vital initiatives to address historical inequalities within the academic sphere.

A key area for student success in UK business schools is closing the BAME awarding gap, also referred to as the ‘degree attainment’ gap - defined as the disparity in degree outcomes between UK-domiciled full-time first-degree students from BAME backgrounds and their White counterparts (UUK, 2022). What continues to hold true is the persistent, statistically unexplained nature of the gap, i.e., even after controlling for other factors (entry qualifications, age, disability, gender, subject studied, school attended and an area participation measure), ethnicity is still statistically significant to the outcomes of a degree award, and it is problematic to determine causality with respect to any single factor (HEFCE, 2015).

The degree awarding gap has remained relatively static at 13% but decreased to 9 percentage points in 2020/21. However, in 2021/22 the gap increased again to 11% (OfS, 2023). The decreases in 2020 to 2021 possibly reflect increased use of coursework and continuous exams to determine qualification awards, and the ‘no detriment’ policies adopted by many HEIs to accommodate for the impact of Covid-19 on students’ performance and experience. Universities UK (UUK) and the National Union of Students (NUS) (2019) argued that universities’ approaches to closing the BAME awarding gap will not succeed unless they are underpinned by strong leadership, with university leaders and senior managers taking personal responsibility for change. We explored to what extent this is happening with the decolonisation and diversification work being undertaken in UK business schools.

*It is important to note that decolonisation and diversification are different concepts and processes. Decolonisation entails dismantling colonial forms of educational practice and knowledge. Diversity is often about adding resources and examples to ensure teaching materials better reflect the staff and student body.

Our research

As members of the Race Equality Action Group (commissioned by the Chartered ABS Equality, Diversity and Inclusion Committee), we knew that work was happening in this space, often supported by a significant investment of time and resource. However, it was unclear what formal evaluation had taken place and to what extent schools and universities were assessing the impact of their interventions. Although there have been UK-based surveys focused on decolonisation of the curriculum including Winter et al.’s (2022) survey of one university, studies have been limited. Whilst Winter et al. surfaced some views on decolonisation and associated social justice themes, no study has focused on business schools at multiple institutions. Consequently, we surveyed Chartered ABS’ members with a short questionnaire (completed by the person with responsibility for curriculum decolonisation/diversification). This survey contains questions including: ‘What interventions does your organisation use to approach decolonisation and diversification of the curriculum’? ‘How are these evaluated’? and, ‘How effective are these methods?

The overarching finding was whilst there has been significant attention given to this work, demonstrated by numerous initiatives (Gopal, 2021), there has been very little evaluation and therefore, limited evidence of meaningful impact. As Peter Drucker said, “What gets measured, gets improved”, but only 40% (11/27 schools) reported that decolonisation/diversification strategies were directly linked to their university’s KPIs, leaving 60% (16 schools) answering ‘no’. When different elements of work were rated, 17 schools (65.4%) responded there was no or limited evidence of ‘measurement and evaluation of initiatives’, and 60% (16) admitted there was no or limited evidence of shared responsibility and accountability. We found few schools have a mature evaluation process in place. If we are asked to account for our time and investment, do we have a robust response?

Business school respondents

Whilst the survey is still live, to date, 27 schools have participated with representation from across the UK. Of the responses received, 18 respondents (67%) reported having a university level strategy for decolonisation/diversification of their programmes, with 8 (30%) stating they did not, while 1 was unsure. At business school level, this increased to 20 (74%) having a strategy, with 7 (26%) reporting ‘no’ or ‘not sure’. Perhaps unsurprisingly, schools have not been engaged in decolonisation/diversification work for long with 42% (11) engaged for 1-2 years, and the same number 3-5 years. Only one school stated they were engaged for 10+ years. Consequently, action and evaluation are emergent rather than embedded, with 81.4% (22) schools stating they felt their institutions had no, limited or some understanding of what decolonisation/diversification is.

Low response rates to the survey may reflect sector-wide disengagement with the decolonisation agenda. Whilst there has been significant coverage, primarily driven by the NUS, this level of student activism is not yet mirrored by universities themselves - Batty (2020) found that only 24/128 UK HEIs were actively pursuing decolonisation as an institutional priority, with only 36/128 offering associated staff development. Although the Race Equality Charter (AdvanceHE) (REC) has helped to provide a clear sector framework, there is only one Silver Award holder (de Montfort University), despite there being 101 REC members, holding 41 awards between them. Furthermore, Winter et al. (2022) point to evidence of limited support to help academics effectively engage with how to offer a (de)colonised curriculum, understand its relevance, and make evidence-informed changes to practice.

When reporting on budget allocations, 67% did not know the budget, 15% admitted there was no budget and only one institution said there was more than £50,000 dedicated to this work. What is equally telling in terms of commitment and priorities, is that whilst 44% stated a deputy/associate dean was leading this work (with a further three stating the PVC/Dean led it), 14 schools stated they had another senior or academic leading this work with 25% stating ‘other’ (these included EDI Directors and Heads of Learning and Teaching). There is clear commitment, but it remains embryonic, and the majority of the work and drive reside in named roles rather than being explicitly led from the top.

Interventions

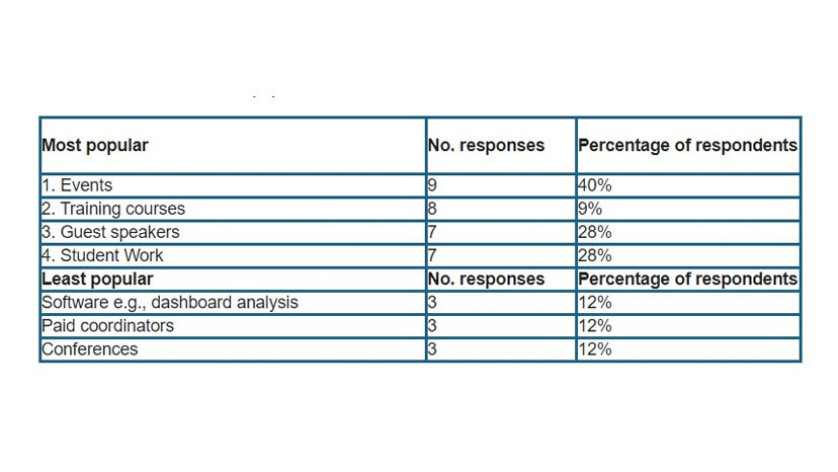

Unsurprisingly, the most popular forms of interventions tend to be those that reach the most staff. The most popular interventions are summarised in Table 1 (multiple responses were permitted and 25 responses were received for this question).

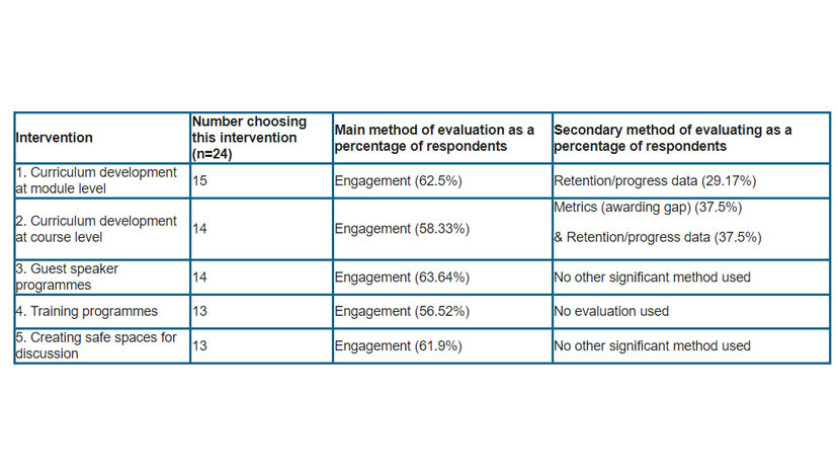

The most common method of evaluation was reported as ‘engagement’ across all listed interventions (Table 2). Whilst events such as guest speaker sessions can attract significant numbers of delegates, there is little evidence that attendance and engagement at an event translated into any meaningful change, action or shift in practice. Likewise, with training programmes or discussions, there were no methods offered that sought to assess whether it led to curriculum change. Whilst most schools are using ‘engagement’ as a proxy evaluation metric, very few state they have converted this into subsequent development of the curriculum. Notably, many respondents stated ‘no evaluation’ was undertaken to monitor the efficacy of any of the interventions. So how are institutions measuring value for money and efficacy of the work done in this area?

Perhaps this reluctance to evaluate interventions reflects a wider lack of enthusiasm in England for decolonising the curriculum. A national survey by Public First for HEPI (UPP Foundation 2021) found that “less than a quarter of the public in England support ‘decolonising’ the curriculum” (23% supported it), with 31% disagreeing with decolonising and 33% neither agreeing nor disagreeing. However, when the same group were surveyed about “broadening the curriculum more generally to take in people, events, materials and subjects from across the world”, 67% supported this position, with just 4% against. This perhaps highlights the importance of better explaining what decolonisation is, why it is important, and using more accessible language and terminology.

Measuring effectiveness

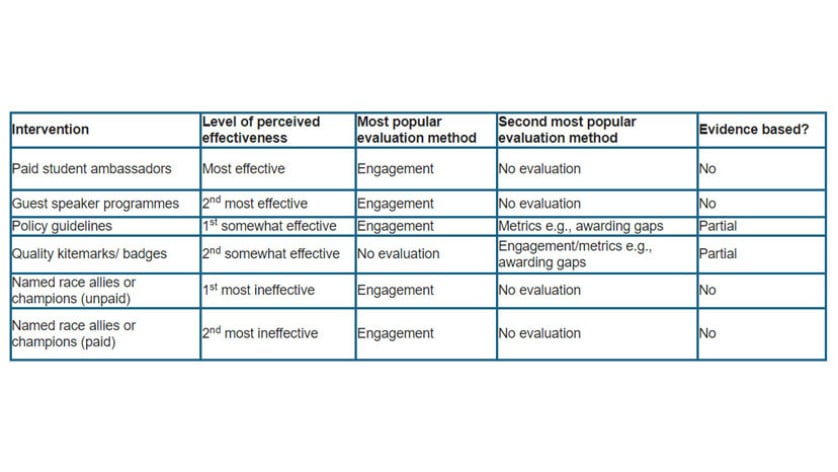

Respondents were asked to rate the effectiveness of interventions (Table 3). Given the main evaluation method was reported to be ‘engagement’, some of the responses about effectiveness were surprising, with the most effective intervention being “paid student ambassadors” at 41% (7 respondents). Surprisingly, only 30% (6 respondents) thought that guest speaker programmes were very effective, despite the main evaluation method being ‘engagement’. The question is why do these institutions regard these interventions as so effective given there seems little evidence base to support this view?

In contrast, the interventions deemed to be least effective are named race allies (unpaid) or champions (unpaid) (40%/5), closely followed by paid named race allies or champions (31%/4). Many respondents chose the middle ground (‘somewhat effective’) with 92% (13) choosing policy guidelines, 60% (12) choosing training programmes and 59% (10) choosing quality marks/kitemarks or badges. These choices are somewhat confusing when correlated against evaluation methods which appear to be very unspecific and immeasurable. Therefore, the perceptions of value of an intervention do not appear to be evidence based.

As Table 3 shows, there is little in the way of evidence-based evaluation of any of the chosen interventions, whether they are seen as effective/ineffective or not. There is a clear need to explore why these choices are being made and whether the funding and time invested in these interventions are being used in the most appropriate ways. Rather, this might evidence a type of ‘decolonial-washing’ that Le Grange et al (2020) suggest is happening. In their study of South African universities, they report similar mechanisms being used for decolonisation to those found in our study i.e. “the use of extensive public lectures, seminars, and workshops as a common strategy to deal with the calls for the decolonising of curricula”, but in an effort to comply, some institutions resort to instrumentalist and quick-fix solutions to decolonise curricula, which result in decolonial-washing rather than substantive change (Le Grange et al., 2020:25). Without rigorous evaluation tools, UK business schools may be in danger of going in the same direction.

Next steps

Chartered ABS member schools are clearly committed to addressing attainment gaps through decolonisation of the curriculum. However, despite significant investment, targeted resources, and a plethora of staff development initiatives, we are yet to see the impact and are unable to evidence what has actually been achieved. The survey has highlighted significant limitations in terms of being able to effectively evidence meaningful impact and positive change. Whilst the recent AdvanceHE (2022) report on differential gaps finds evidence that work addressing the ethnicity degree awarding gap is starting to make a difference in the university sector, it also states that there is “still some distance to go as evidenced by UK domiciled Black qualifiers who remained far less likely to be awarded a First or 2:1 than any other ethnic group”.

Although the sample is small, results highlight the importance of ensuring well-intentioned interventions can be meaningfully evaluated from the outset. Our small survey has highlighted the value of putting in place explicit evaluative measures and tools from the start. We hope we can work together to help share ways that can assess the effectiveness and impact of decolonisation projects before we invest resources in them.

If you are interested in contributing and sharing ideas about how our community can more effectively evaluate the interventions, then we will be running a roundtable at the Chartered ABS Annual Conference in November. Furthermore, if you are yet to complete the survey on behalf of your business school, then the survey is still open and can be completed here.

References

AdvanceHE (2022) Equality in higher education: statistical reports 2022. Accessed: https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/news-and-views/equality-higher-education-statistical-reports-2022

Batty, D. (2020). Only a fifth of UK universities say they are ‘decolonising’ curriculum. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/jun/11/only-fifth-of-uk-universities-have -said-they-will-decolonise-curriculum

Gopal, P. (2021) On Decolonisation and the University. Textual Practice, 35 (6), 873-899, DOI: 10.1080/0950236X.2021.1929561

HEFCE (2015) Causes of Differences in Student Outcomes. Available: https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/id/eprint/23653/1/HEFCE2015_diffout.pdfLe Grange, L.; Du Preez, P.; Ramrathan, L.;Blignaut, S. (2020) Decolonising the university curriculum or decolonial- washing? A multiple case study. In Journal of Education 80(80), 25-48. DOI 10.17159/2520-9868/i80a02

McDuff, N. and Barefoot, H. (2016) It’s time for real action on the BME attainment gap. Available: http://wonkhe.com/blogs/analysis-time-for-real-action-on-bme-attainment

Office for Students (2021) Students need support to succeed in and beyond higher education. Available: https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/news-blog-and-events/press-and-media/students-need-support-to-succeed-in-and-beyond-higher-education/

UPP Foundation (2021) Public’s views on decolonising the curriculum depend on how changes are presented. Available: https://upp-foundation.org/publics-views-on-decolonising-the-curriculum-depend-on-how-changes-are-presented/

UUK (2022) Closing the Gap: Three Years on. Available: Closing the gap: three years on (universitiesuk.ac.uk)

UUK & NUS (2019) Closing the Gap. Available: https://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/sites/default/files/field/downloads/2021-07/bame-student-attainment.pdf

Winter, J., Webb, O. & Turner, R. (2022) Decolonising the curriculum: A survey of current practice in a modern UK university. Innovations in Education and Teaching International. DOI: 10.1080/14703297.2022.2121305